Ocean Voices – Education to decrease noise impacts to marine mammals

Living in a world of sound

Most animals that live in the ocean rely on sound for their survival. Marine mammals in particular use sound to navigate, find food, and communicate. While marine mammals have good eyesight, their vision is often limited because light does not penetrate water very far. Their vision is often limited further by the amount of plankton and turbulence in the water.

Sound, however, travels well in water, approximately 5 times faster and much further than in air. This allows marine mammals to use sound over great distances. It also means that noise can travel far and have significant negative impacts on the ability of marine mammals to communicate, rest, mate, establish territory, navigate, socialize, hunt, and avoid predation and other dangers.

Human-made noise results from a wide range of activities such as boating and shipping, coastal development, and resource exploration and extraction.

Click here to Listen to Whales

Click here for Laws and Boater Safety

Click here for more MERS videos related to ocean noise and sound in the sea.

Why human-made ocean noise is a problem

Underwater noise affects the ability of marine mammals to both receive and transmit sound. In other words, it impacts their ability to hear and be heard. Especially loud, repeated, and long-lasting exposure to noise can significantly impact many life processes, and exacerbate the effects of other threats such as reduced prey availability and chemical pollution.

Underwater noise is linked to a wide range of possible impacts on marine species including:

- Disruption of their behaviour

- Loss of habitat

- Masking sound transmission and reception

- Changes to their physiology and/or increased stress levels

- Temporary or permanent hearing impairment

- Permanent injury or even death

How marine mammals use sound

Examples of how marine mammals off the coast of British Columbia rely on sound

Seals and Sea Lions:

- Harbour Seal males establish acoustic territory with vocals known as roars.

- Harbour Seals are capable of complex acoustic discrimination. They are known to selectively habituate to the calls of familiar fish-eating Orca . They only react strongly and adversely when they hear the calls of mammal-hunting Orca (Bigg’s) or unfamiliar fish-eating Orca.

- Mother Steller Sea Lions and California Sea Lions are known to have “pup-attraction calls” to help mother and pup find one another.

Orca:

- Northern and Southern Resident Orca are fish-eaters that use echolocation to locate and identify their prey. They are even able to discern different species of salmon using echolocation. The most important prey for their survival are Chinook Salmon, followed by Chum Salmon.

- Different Orca populations have different languages. This is believed to help ensure they do not breed outside their populations e.g. Southern Residents only mate with Southern Residents and Northern Residents only mate with Northern Residents. By only mating with Orca in the same population (who have the same language) their distinct cultures are maintained e.g. mammal-hunting Orca need to live very differently than fish-eating Orca.

- Within Resident Orca populations (inshore fish-eaters), there are different dialects. These differences within the language are believed to be important to avoid inbreeding.

For example, every Northern Resident matriline has specific calls. A matriline is a stable social unit made up of a mother, her sons and daughters and her daughters’ offspring. The calls are passed on from mother to offspring ensuring all members of the same matriline sound the same. The more closely related Northern Resident matrilines are, the more similar their calls are i.e. there is a direct correlation between acoustic similarity and degree of relatedness.

Recognizing vocal similarities and differences is believed to affirm relatedness and avoid inbreeding. Research supports that Northern Residents who sound exactly the same are members of the same matriline; they stay together; and do NOT mate with one another. The greater the vocal differences between Northern Residents matrilines, the more distantly they are related, whereby mating would not lead to inbreeding. Note that the Orca do not leave their matrilines to mate, the matrilines group together.

Note that there are also differences in dialects in the endangered Southern Resident Orca population. There are vocal differences between members of the three Southern Resident pods (J, K and L) and there are likely also acoustic differences between matrilines. Resident Orca in Southern Alaska also have distinct dialects and separate vocal clans.

Porpoise:

- The frequency range of Harbour Porpoise echolocation clicks is outside the hearing range of one of their predators, mammal hunting Orca (Bigg’s Killer Whales). It is likely also the case that the vocals of Dall’s Porpoise are outside the hearing range of mammal-hunting Orca.

Minke Whales:

- Minke Whales use very distinct calls, known as “boings”, in the warm-water breeding grounds. When in the cold-water feeding grounds, they are not known to make this call. Rather, they appear to use very different calls and vocalize far less frequently. This may be to avoid detection by mammal-hunting Orca in the feeding grounds.

Humpback Whales:

- The vocalizations of Humpback Whale mothers include calls to stay in contact with their calves.

- Humpback Whales who work together in a group to bubble-net feed use an acoustic signal to coordinate the feeding strategy and/or to help concentrate the small schooling fish e.g. Pacific Herring.

- Male Humpback Whales produce songs that are considered amongst the most intricate acoustic displays in mammals. They learn their songs socially, much like humans and all males in one breeding ground sing the same song. If the song changes, they all adopt the change.

- Male Humpback Whales sing in both the feeding grounds and breeding grounds. Theories for the purpose of the song are that it has a role in male-male relationships; attracting mates; and possibly establishing territory in the warm water breeding grounds.

How to reduce noise

There is much that can be done to reduce ocean noise caused by marine traffic.

1) Give them space

The further away vessels are from marine mammals, the less the impacts are from noise. The risk of collision is also reduced.

There are laws about how far to stay away from marine mammals. This includes staying 400 metres away from Orca in southern British Columbia and staying at least 200 metres away elsewhere, especially when there are resting whales or whales with calves. If, despite your vigilance, a whale surfaces within the legal distance, put your engine in neutral and only slowly proceed when you are sure the whale is beyond the legal distance.

By knowing the laws and best practices, you are not only reducing your impacts, you are helping by modelling good boater behaviour to others.

Click here for Laws and Boater Safety

2) Slow down

It is almost always the case that when vessels slow down, noise is reduced. Slowing down also reduces the risk of collision* and lowers fuel consumption and engine emissions.

“Be Whale Wise” best practices to reduce noise impacts to Orca include:

- Reduce speed to less than 7 knots when within 1,000 metres

- Turn off echo sounders and fish finders if safe to do so

- Place engine in neutral when, despite best efforts to maintain legal distances, animals are near

Current slow down and sanctuary zones off the coast of BC that are aimed at reducing impacts to Orca:

- Michael Bigg Ecological Research Robson Bight in Johnstone Strait

- Interim sanctuaries in the Southern Gulf Islands

- Swiftsure Bank slow down zones

- ECHO Program voluntary slow down zones for large vessel traffic

*With the fortunate recovery of Humpback, Grey, and Fin Whales from whaling, there is greater overlap between these large whale species and vessels. This necessitates measures to reduce the threats of collision and noise.

3) Whale Warning Flag

Through raising the Whale Warning Flag, you signal to other boaters that there are whales in the area and that it is necessary to increase vigilance and slow down.

4) Turn down the volume

Well-maintained engines tend to be less noisy. Four-stroke engines are usually quieter than two-stroke engines and also create fewer emissions.

Additionally, clean hulls and propellers cause less drag, and therefore less noise. Damaged propellers, shafts and axles tend to produce sounds that can interfere with the whales’ vocalizations and can increase stress.

Ideally use vessels with optimized noise reduction designs, including propellers with reduced cavitation. Cavitation is often related to the specific rotation speeds of propellers, measured in revolutions per minute (RPM). Operators can reduce noise by knowing at what RPM their vessel’s propeller starts producing cavitation sounds.

Note that technological advances must consider that motorized vessels that are completely silent / stealth may increase the risk of collision with whales.

5) Consumer clout

When more people care about the impacts of ocean noise, there is greater motivation to design quieter vessels and engines.

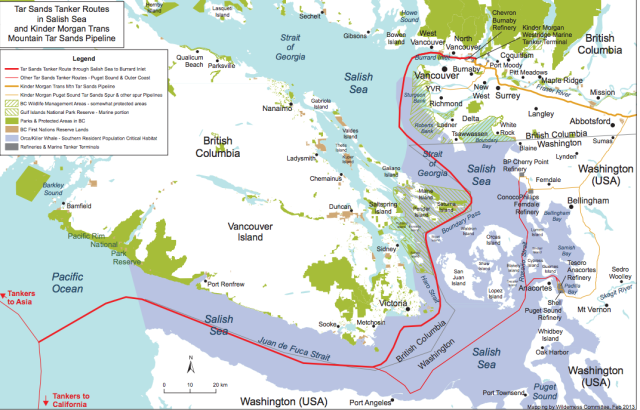

But you don’t need to be a boater to make a difference. Our daily consumer and energy-use decisions impact how much noise is in the ocean. Large vessel traffic, such as tankers and cargo ships, is reduced through buying less and from closer to home, and by reducing use of fossil fuels.

6) Shout it out

The more people care about ocean noise, and the many solutions to reduce the impacts, the more we are helping shape values, voting behaviour, policies, and technological advances.

The Science of Sound

Sound travels much faster in water than in air. The radiated sound energy is measured in decibels and changes with speed and distance between the source of the sound (e.g. vessel) and the receiver (e.g. whale). Generally, sound travels approximately 5 times faster in water than in air but this varies depending on temperature, depth/pressure and salinity.

Initiatives to document noise off the coast of British Columbia

The British Columbian Hydrophone Network, also known as “Whale Sound”, is a collaboration of First Nations and non-governmental agencies to build, maintain, and contribute to a shared, coast-wide acoustic information system. Collecting acoustic and visual data on whale activity using consistent standards and protocols, via professionally maintained and consistently calibrated equipment, will enable (1) the quantification of how the ocean soundscape is changing; and (2) a comparison of vessel traffic impact on whales in areas that differ environmentally and acoustically.

The high-quality, comparable ocean acoustic datasets gathered by Network members will be archived using a centralised database and will be available for scientific, stewardship, and/or educational purposes.

NoiseTracker will be a publicly available website and map-based noise visualization tool that brings together the efforts of those measuring noise off the coast of British Columbia. NoiseTracker will allow for:

- Identification of acoustic disturbance hotspots—places where high levels of noise and high biological productivity coincide.

- Evaluation of the effectiveness of noise mitigation measures by documenting changes in noise levels over time.

- Development and implementation of additional measures to reduce ocean noise.

Acknowledgements:

Financial support for Ocean Voices was provided by the North Island Marine Mammal Stewardship Association’s Conservation Fund (NIMMSA).

Guidance and expertise were provided by Helena Symonds, Co-founder of OrcaLab; Dr. Valeria Vergara, Co-director of Raincoast Conservation Foundation’s Cetacean Conservation Research Program; and Dr. Harald Yurk, Bioacoustician / Biophysical Scientist with Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Animations made by Dawn Dudek with sound from OrcaLab.

Dive Deeper:

- Burnham, R. E., Vagle, S., Thupaki, P. and Thornton, S. 2023. Implications of wind and vessel noise on the sound fields experienced by southern resident killer whales Orcinus orca in the Salish Sea. Endangered Species Research, 50: 31-46.

- Deecke, V., Slater, P. & Ford, J. Selective habituation shapes acoustic predator recognition in harbour seals. Nature 420, 171–173 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01030

- Discovery of Sounds in the Sea (DOSITS)

- Dugald J. M. Thomson, David R. Barclay; Real-time observations of the impact of COVID-19 on underwater noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1 May 2020; 147 (5): 3390–3396.

- Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation (ECHO) program – resources for mariners

- Fournet MEH, Matthews LP, Gabriele CM, Haver S, Mellinger DK, Klinck H (2018) Humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae alter calling behavior in response to natural sounds and vessel noise. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 607:251-268.

- Haver, Samara & Gustafson, Kyle & Gabriele, Chris. (2023). Rapid assessment of vessel noise events and quiet periods in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve using a convolutional neural net. Environmental Data Science. 2. 10.1017/eds.2022.36.

- Heise, K.A., Barrett-Lennard, L.G., Chapman, N.R., Dakin, D.T., Erbe, C., Hannay, D.E., Merchant, N.D., Pilkington, J.S., Thornton, S.J., Tollit, Veirs, V.R., Vergara, V., Wood, J.D., Yurk, H. 2017. Proposed Metrics for the management of underwater noise for Southern Resident Killer Whales. Coastal Ocean Institute Report Series 2, Vancouver, 30pp.

- Holt, M. M., Tennessen, J. B., Hanson, M. B, Emmons, C. K., Giles, D. A., Hogan, J. T., Ford, M. J. 2021. Vessels and their sounds reduce prey capture effort by endangered killer whales (Orcinus orca). Marine Environmental Research 170: 105429.

- Holt MM, Noren DP, Veirs V, Emmons CK, Veirs S. Speaking up: Killer whales (Orcinus orca) increase their call amplitude in response to vessel noise. J Acoust Soc Am. 2009 Jan;125(1):EL27-32. doi: 10.1121/1.3040028. PMID: 19173379.

- Lemos, L.S., Haxel, J.H., Olsen, A. et al.Effects of vessel traffic and ocean noise on gray whale stress hormones. Sci Rep 12, 18580 (2022).

- Rolland RM, Parks SE, Hunt KE, Castellote M, Corkeron PJ, Nowacek DP, Wasser SK, Kraus SD. Evidence that ship noise increases stress in right whales. Proc Biol Sci. 2012 Jun 22;279(1737):2363-8. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2429. Epub 2012 Feb 8. PMID: 22319129; PMCID: PMC3350670.

- Thornton, S.J., Toews, S., Burnham, R., Konrad, C.M., Stredulinsky, E., Gavrilchuk, K., Thupaki, P., and Vagle, S. 2022. Areas of elevated risk for vessel-related physical and acoustic impacts in Southern Resident Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) critical habitat. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2022/058. vi + 47 p.

- Vagle, S., Burnham, R. E., O’Neill, C., & Yurk, H. (2021). Variability in anthropogenic underwater noise due to bathymetry and sound speed characteristics. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 9(10), 1047.

- Vergara, V., Wood, J., Lesage, V., Ames, A., Mikus, MA., and Michaud, R. 2021. Can you hear me? Impacts of underwater noise on communication space of adult, sub-adult, and calf contact calls of endangered St. Lawrence belugas (D. leucas). Polar Research 40, 5521.

- Wisniewska Danuta Maria,Johnson Mark,Teilmann Jonas,Siebert Ursula,Galatius Anders,Dietz Rune andMadsen Peter Teglberg. 2018. High rates of vessel noise disrupt foraging in wild harbour porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) Proc. R. Soc. B. 2852017231420172314

- Yurk, Harald & O’Neill, C. & Quayle, L. & Vagle, Svein & Mouy, Xavier & Austin, M. & Wladichuk, J. & Morrison, C. & LeBlond, W.. (2023). Adaptive Call Design to Escape Masking While Preserving Complex Social Functions of Calls in Killer Whales. 10.1007/978-3-031-10417-6_187-1.

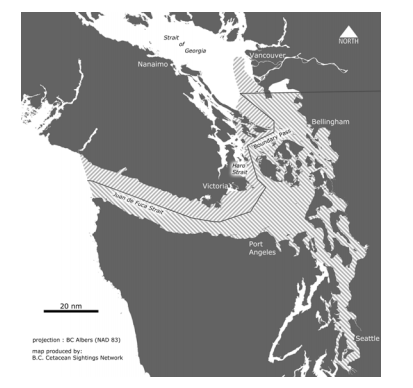

![Figure 3: “Map showing the habitat considered necessary for meeting recovery objectives for inner coast WCT killer whales [West Coast Transient]. Area includes marine waters bounded by a distance of 3 nautical miles (5.56 km) from the nearest shore. This area includes the locations of over 90% of all individual identifications and predation events documented in BC waters during 1990-2011.” Source: Ford, J.K.B, E.H. Stredulinsky, J.R. Towers and G.M. Ellis. 2013. Information in Support of the Identification of Critical Habitat for Transient Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) off the West Coast of Canada. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2012/155. iv + 46 p. http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Csas-sccs/publications/resdocs-docrech/2012/2012_155-eng.pdf](https://mersociety.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/screen-shot-2016-11-30-at-11-20-19-pm.png)

![Figure 4: “Locations of the four critical habitat areas [for humpback whales]: a. Southeast Moresby Island, b. Langara Island, c. Southwest Vancouver Island, d. Gil Island (DFO 2009). The existence of other areas of critical habitat for Humpback Whales in B.C. is likely.” Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2013. Recovery Strategy for the North Pacific Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. x + 67 pp. http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/plans/rs_rb_pac_nord_hbw_1013_e.pdf](https://mersociety.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/screen-shot-2016-11-30-at-11-10-51-pm-e1480623045844.png?w=640)