Can you imagine what our team felt when we heard Sir David Attenborough say the name of Conger the Humpback Whale? That happened when episode 7 (Human) of the BBC’s Planet Earth III aired in Europe on December 3rd. Sir David said the name of Conger, a whale we nicknamed in 2009, the first year we ever saw him (Conger’s catalogue designation is BCY0728).

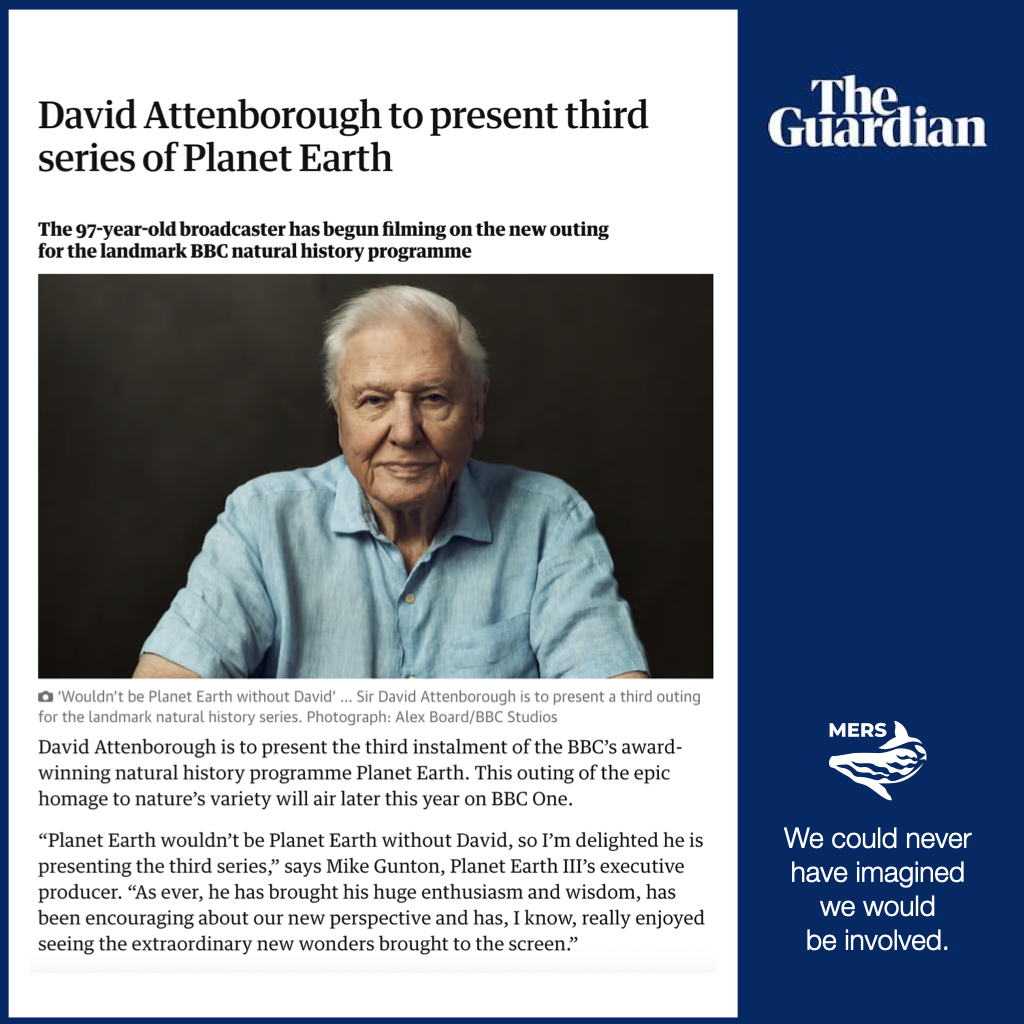

We worked with the BBC in 2021 and 2022 to film the Humpbacks who return to feed around northeast Vancouver Island in the Territory of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw (the Kwak̕wala-speaking Peoples). The hope is that the global reach of Planet Earth III will lead to significant positive action for conservation.

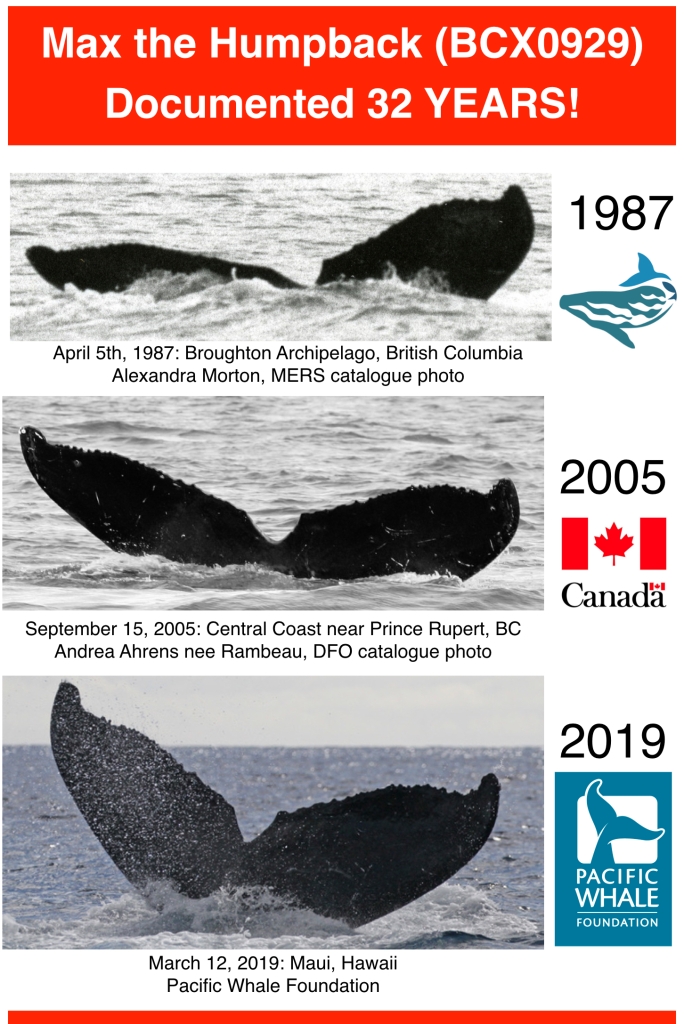

That moment when David Attenborough said “Conger” was the culmination of so many years where we have worked to increase understanding of the whales as individuals. Who they are – their life histories, feeding strategies, habitat use, relationships, and how they are impacted by threats such as collision and entanglement. In our education efforts, we speak about who the whales are, using their nicknames, to create connection and care about them as individuals. Conger is nicknamed for an eel-like marking on the underside of his tail; a shape like Conger Eel.

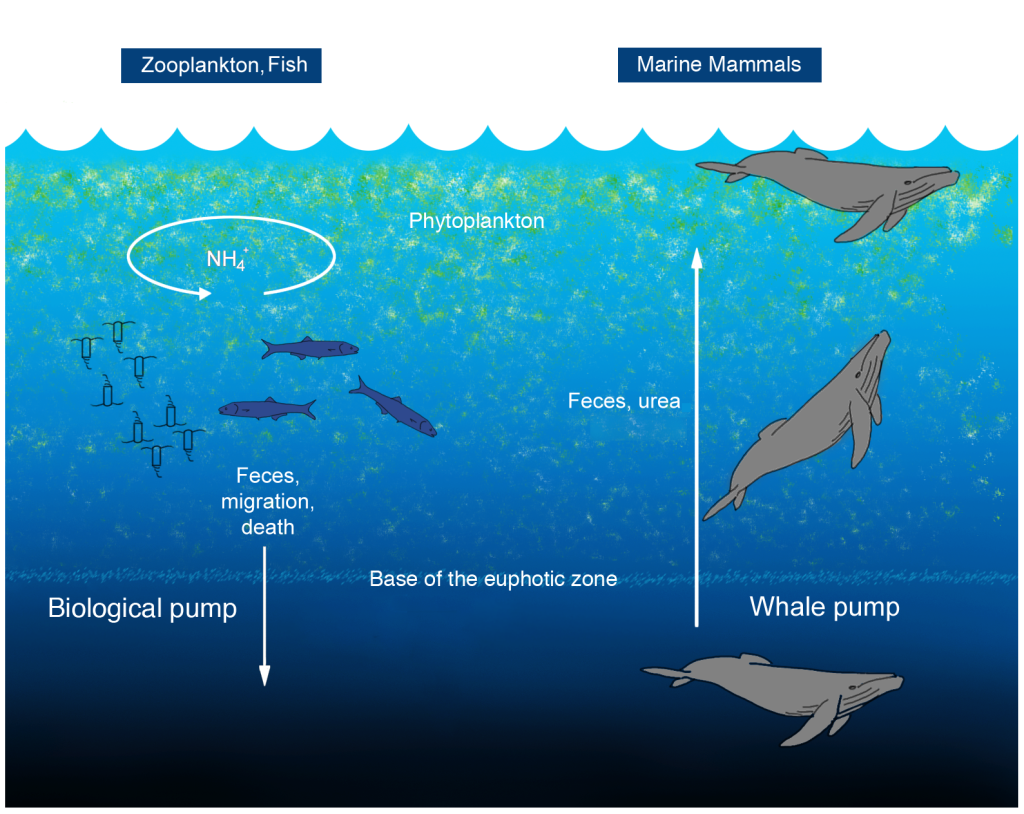

The main conservation message of the Planet Earth III segment featuring the Humpbacks we study was about the importance of individual whales – that every large whale helps life on Earth by sequestering approximately 33 tons of carbon from the atmosphere (the equivalent of 30,000 trees).

But . . . why Conger?

Why, of all the Humpback Whales from whom we have learned and who were filmed by the BBC, was Conger the lead ambassador? Many other whales also return to the area near northeastern Vancouver Island to feed and we would also be able to anticipate and interpret their behaviour for the film crew.

It’s because Conger was the first whale we ever saw trap-feeding. This feeding behaviour had never been seen anywhere else in the world with any other Humpback before we documented it in 2011 with Conger. This is what initially drew the attention of the BBC. We published on trap-feeding and continue to document which whales learn this behaviour.

So it was Conger who was the whale who we most often focussed on (literally) with the film crew. Filming him using this new feeding strategy would lead to talking about the importance It was important to get footage of him trap-feeding and lunge-feeding. See here for the difference in those behaviours.

But, very unexpectedly, it became extremely challenging to film Humpbacks feeding near the surface in September 2021. This was NOT because of Conger. Rather, there was an “intrusion” of a species of bird that changed things. Short-tailed Shearwaters (Ardenna tenuirostris) came into the area in the thousands. Commonly, they are in huge numbers further to the north. But this had never been documented before around northeast Vancouver Island.

How did they change the dynamics of Humpback feeding? The diving bird species that are usually in the area, namely Common Murres and Rhinoceros Auklets, coral juvenile Herring near the surface into a big ball. Gulls also try to snatch the Herring being pushed to the surface by these diving birds. Humpbacks target these “Herring balls” – engulfing the ball when they lunge-feed. Or, if the Herring are in a less concentrated aggregation, the whales might trap-feed.

However, the Shearwaters “bomb” the juvenile Herring at the surface, splitting up the ball and driving the Herring deeper. Thereby, there was far less feeding at the surface by Humpbacks.

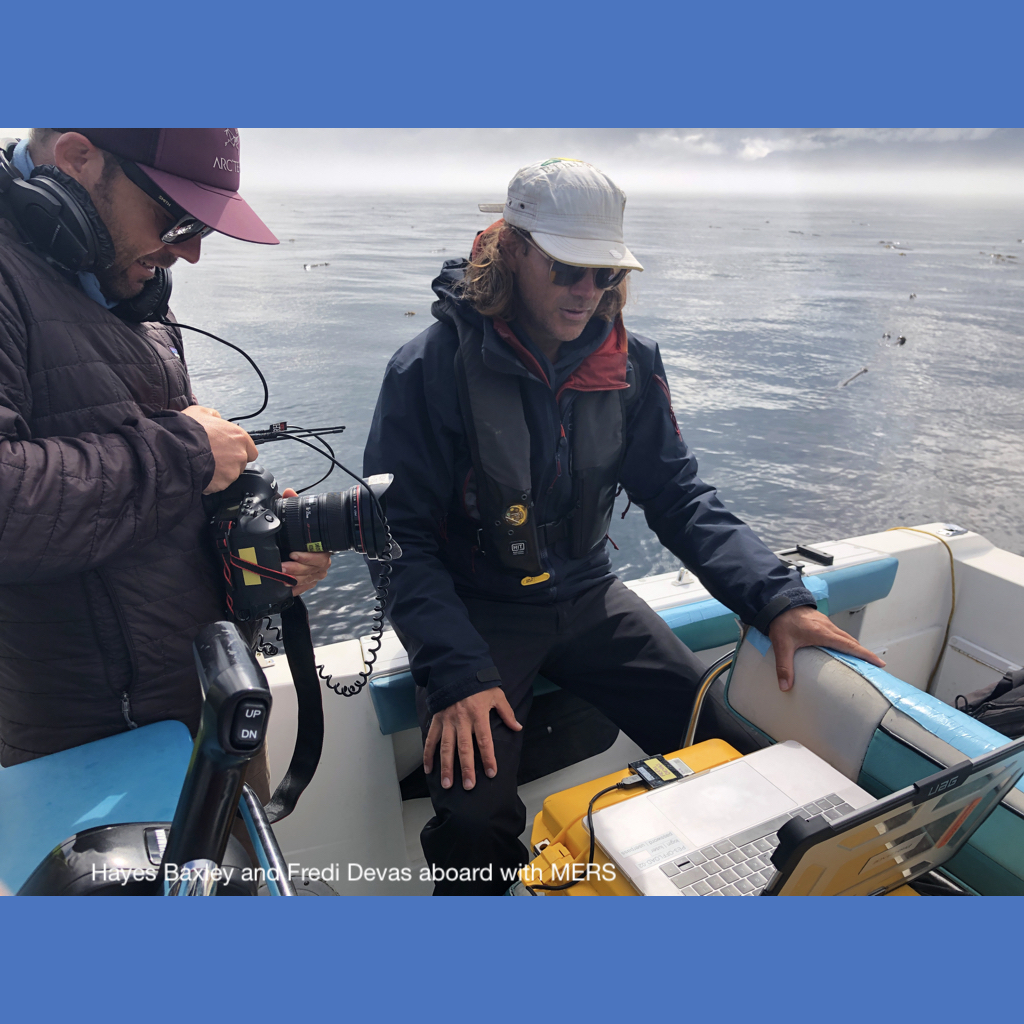

This led to us having the joy of a second session of filming with the BBC. In 2022, in the absence of Short-tailed Shearwaters, abundant Humpback feeding was filmed. We spent so much time observing Conger with the film crew when they were using a drone to capture his behaviour, that we laughingly referenced that we were often “in a Conger line” (a word play on being in a conga line).

With Conger being such a powerful ambassador for whales, their sentience, and how they contribute to life on Earth, he is now one of our sponsorship whales. Through sponsorship, you get a detailed backgrounder about Conger, receive updates about him, and support our work to reduce threats to the whales. Please learn more about our Humpback sponsorship program at this link.

___________________________________

Related links:

- The Making of Planet Earth III – A second chance with giants: Learning from humpback whales

- How we nickname and catalogue Humpback Whales

- Trap-feeding – our research paper with videos

- How you can help the whales, wherever you are

- Our Humpback Whale sponsorship program

___________________________________

Episode 7 of Planet Earth III “Human” also airs on :

- December 16, 2023 via BBC America

- April 21, 2024 in Canada

On the production we worked with:

- Fredi Devas, producer, whose work includes BBC’s “Seven Worlds One Planet”, Planet Earth II “Cities”, and “Frozen Planet”.

- Bertie Gregory, film-maker whose work includes BBB’s “Seven Worlds One Planet”, and star of National Geographic’s “Epic Adventures with Bertie Gregory”.

- Hayes Baxley, cinematographer whose work includes Emmy award-winning “Secrets of the Whales” (Disney +).

- Tavish Campbell, dear friend of MERS and a BC cinematographer deeply dedicated to conservation on our coast.